U.S. Seeks Overhaul of UN Amid Calls for Accountability

By Hugh Dugan

Tuesday, 23 September 2025 04:01 AM EDT

Riddled by financial crisis and staff trust in its Secretary-General at an all-time low of 18%, the United Nations soon hosts its annual speechathon. It’s 80 years old this October and showing every bit of its age—poor footing, lost resilience, and speaking always in the past tense. Critical eyes are cast instead upon U.S. President Trump’s foreign agenda. All are asking, “What’s the U.S. thinking about the future of the United Nations and multilateralism in general?”

The United States is not stepping back from the UN—rather the U.S. wants it to succeed and is willing to step up to reshape it. In February, U.S. President Donald Trump said, “I’ve always felt that the UN has tremendous potential. It’s not living up to that potential right now… it hasn’t for a long time.” He ordered a study to see how that potential might be tapped.

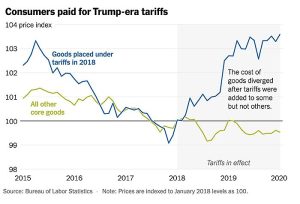

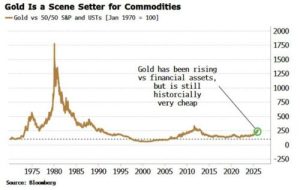

Trump is signaling that the U.S. remains at the table—but only where the terms deliver results. Every UN dollar now comes with a scoreboard—and the U.S. is keeping the pen. As this writer sees it, the U.S. has shifted from “loving or leaving it” to supporting the UN when it works and when it works for us. Funding, oversight, and reform demands are America’s levers and sticks.

This reminds me of persistent congressional frustration with UN waste. For example, in 2000, Helms-Biden legislation put such sticks to work. Eventually, the UN received $1 billion in carrots that the U.S. had held back under Democrat Bill Clinton. The United States is back at the United Nations—something Biden tried to claim by going along to get along.

President Trump returns to the only proven default to continue U.S. participation at the UN: be transactional and let the results determine future U.S. support and engagement there. Instead of abandoning the UN as a distressed property, New York real estate developer Trump would rather remake the UN house into his wheelhouse.

As for participating in the Security Council, the U.S. stays fully engaged but on its terms. But most UN offices are in the White House’s conditional zone. A few are clearly out of the administration’s favor, such as the UN Human Rights Council whose membership continues to include “foxes guarding the henhouse.”

Most headlines put the weapon of the UN’s end in Trump’s hands. In fact, he is open to seeing it perform and willing to set consequences otherwise. Every member state should be doing the same. But when the U.S. does so, we get labeled as hostile and world-destabilizing. If fact, we should be credited for promoting improved stewardship over a slow-go UN and its peri-pandemic staff still phoning it in from home.

Why else would Trump be sending an “A” team—an Ambassadorial team—of heavyweights headed up by warrior Mike Waltz to the United Nations? The UN’s relevance, as that of many other multilateral organizations, is at stake.