Productivity Surge Threatens to Outpace U.S. Job Growth, White House Economic Adviser Warns

Monday, February 9, 2026

White House National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett warned Monday that U.S. job gains could decline in the coming months due to slower labor force growth and rising productivity—a development intensifying debates at the Federal Reserve and promising significant influence over the central bank’s upcoming policy decisions.

Monthly payroll employment grew by an average of 53,000 positions in November and December, compared to a steady monthly gain of 183,000 jobs over the decade prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and significantly higher numbers during recent economic booms under the Biden administration.

Hassett noted some of this job growth was fueled by an influx of workers due to expansive immigration policies—a trend President Donald Trump has recently reversed—complicating economists’ efforts to determine whether the labor market’s slowdown stems from weakening economic conditions or insufficient workers filling available positions.

The White House National Economic Council director provided a third explanation: heightened productivity—meaning each worker produces more—could enable continued economic expansion even with fewer employees and modest monthly job gains.

Hassett emphasized that strong GDP growth combined with a sharp decline in the labor force “due to undocumented migrants leaving the country” could lead to lower employment figures.

“ heatedly, you should expect slightly smaller job numbers consistent with current high GDP growth,” Hassett stated during a recent interview. “We shouldn’t panic if you see a sequence of numbers below what you’re used to, because population growth is declining and productivity is skyrocketing—a situation that’s unusually complex.”

The U.S. Labor Department is set to release its delayed January employment report on Wednesday. A recent survey of economists indicated nonfarm payrolls likely rose by 70,000 in December—up from 50,000 in the previous month—and the unemployment rate remained at 4.4% in December, with expectations for no change in January.

Hassett’s comments align with Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s recent remarks following the central bank’s latest policy meeting. Powell described a “very challenging and quite unusual situation” where both demand and supply of workers are falling.

This scenario could manifest as slower-than-typical job growth while maintaining a steady unemployment rate, making it difficult for policymakers to interpret labor market trends. Powell highlighted that the Fed’s response would depend on whether constraints lie in worker supply or economic demand. If supply is limited due to deportations, it might trigger hiring bottlenecks and higher wages—potentially leading to inflation and delaying interest rate cuts. Conversely, if job growth weakens from low demand, the Fed may lower rates to stimulate activity.

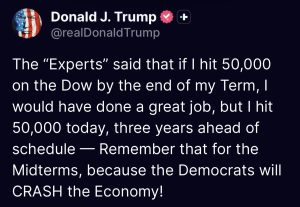

President Donald Trump has criticized Powell and the central bank for failing to deliver deep rate cuts he believes are necessary to boost the economy.

Similarly, Federal Reserve nominee Kevin Warsh—recently named by Trump to replace Powell in May—is also suggesting that elevated productivity could dampen inflation and alter the Fed’s policy trajectory.

While Powell and most Fed officials acknowledge the possibility of sustained high productivity, they remain cautious about basing short-term decisions on this trend alone.

“The demand versus supply question is critical for monetary policy,” said Dario Perkins, managing director of global macro at TS Lombard. “If it’s demand, the Fed needs to act. If it’s supply, inflation will be stickier, and the Fed should hold firm.”

Perkins added that with existing demand stimulus already en route, a constrained labor supply could create complications.